The following is a GUEST-POST composed by Dr. Sascha Tuchman, a friend and colleague from the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, NC. Dr Tuchman will be co-moderating the final pre-ASH 2018 #amyloidosis journal club (#amyloidosisJC) with Untangling Amyloidosis 208 Trainee Travel Grant Awardee Dr. Sam Rubinstein

|

| Dr Tuchman |

|

| Dr Rubinstein |

Background:

For basic information on transthyretin

(TTR) and how it forms amyloidosis, please refer to the background information

in recent blog post dated 10/28/18, which summarized the APOLLO study of patisiranin hereditary transthyretin polyneuropathy.

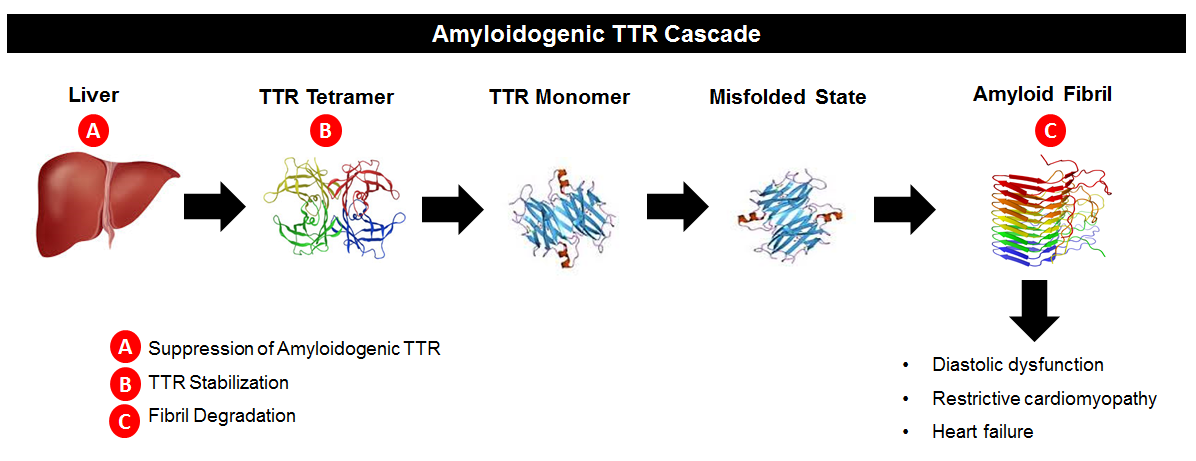

Drugs like patisian work to suppress TTR synthesis by the liver (“A” in

the below diagram). Another area of research interest has been in TTR stabilizers.

If we refer to the image below, we see that TTR circulates in blood as a

tetramer, meaning a single molecule made up of four pieces of TTR joined together.

The TTR tetramer dissociates, resulting in single TTR pieces (monomers). Those monomers can deposit in organs and form

amyloid. The theory behind TTR

stabilizers is that making it harder for the tetramers to dissociate means

there are fewer TTR monomers available to form amyloidosis (“B” in the below

diagram). The “B” approach was first successfully tested using the drug diflunisal

in patients with TTR neuropathy (Berk J et al., JAMA 2013). The current “ATTR-ACT” study examined the oral

TTR stabilizer tafamidis in patients with TTR amyloid cardiomyopathy.

The above image is copied from: https://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2015/10/13/08/35/emerging-therapies-for-transthyretin-cardiac-amyloidosis

Methods:

Phase 3, international study of 441 patients

with biopsy-proven TTR cardiac amyloidosis. Placebo-controlled and

double-blinded. Patients had to have

clinical evidence of active heart failure, but less severe than symptomatic at

rest (NYHA class <4). Severe

impairment of liver/kidney function or nutritional status precluded

participation. Patients were prohibited

from receiving other TTR-directed agents such as diflunisal or

doxycycline during study participation.

Patients received either 80 or 20 mg of tafamidis daily orally

or placebo (randomized in a 2:1:2 ratio). Stratified by TTR mutational status

(wild-type vs mutated) and baseline NYHA class. Treatment was for 30 months and

on completion, patients could opt to continue on to an extension study

including open label tafamidis.

The primary endpoint was all-cause mortality followed by

cardiovascular-related hospitalizations.

The planned sample size of 400 patients was 90% powered to detect a 30%

reduction in mortality and in cardiovascular-related hospitalizations from 2.5

to 1.5 over the 30 months on study.

Results:

548 patients screened and 441 randomized.

264 patients received tafamidis and 177 placebo. ~24% in both groups had

mutated TTR, with a similar frequency of specific TTR mutations in each group.

Other baseline factors were similar, including NYHA class, NT-proBNP, and body

mass index (BMI).

Both mortality and frequency of cardiovascular-related

hospitalizations were improved with tafamidis. Specifically the hazard ratio

for all-cause mortality was 0.7 (95% CI 0.51-0.96) and the relative risk for

hospitalizations was 0.68 (0.56-0.81).

The mortality benefit appeared after approximately 18 months on study. Benefits

were consistent across all subgroups except NYHA class 3 CHF, in which

mortality was the same but rate of hospitalizations was higher for tafamidis.

Functional measures of the heart also showed a slower

decline with tafamidis than placebo, such as distance walked in 6 minute walk

test and patient-reported symptoms.

There were no significant adverse events for tafamidis, and

discontinuation from study as a result of adverse events was more common for

placebo-treated than tafalidis-treated patients.

Conclusions:

Tafamidis reduced mortality and

cardiovascular-related hospitalization in patients with cardiomyopathy

resulting from either wild-type or mutated TTR.

Markers of heart function such as 6 minute walk test and NT-proBNP

suggest that tafamidis doesn’t stop the disease, rather it slows its

progression.

Comments:

Tafamidis is clearly a game-changer in the

sense that it’s the first medication that will likely be FDA-approved for TTR

cardiomyopathy. However, the fact that the disease still progresses indicates

that more needs to be done. In particular, combining tafamidis with drugs that

perturb other aspects of TTR formation could be promising. (Recall in the

diagram above that tafamidis is a “B” drug.

Other drugs such as patisiran and inotersen are “A” drugs. Combining a B drug with an A drug and/or a C

drug may improve the benefit overall to patients with these diseases by further

slowing or even reversing damage caused to the heart by TTR.)

EDITOR'S ADDENDUM: looking forward to this week's installment of #amyloidosisJC, at 8 pm EST on Sunday November 18, 2018. Remember to use the #amyloidosisJC hashtag when you log on! Also, hoping to see you in San Diego for the Untangling Amyloidosis 2018 Friday Satellite Symposium. Turns out Dr Tuchman is joining the faculty speaker roster!